SCHEIN ON

Jim Connor • May 17, 2019

What culture has for breakfast

Parents, particularly according to Philip Larkin, have a lot to answer for. But in the case of Edgar Schein, his parents deserve high praise for his effortlessly cool and stylish name which almost certainly set him up for future success.

Born in 1928, Schein was a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and made his mark through his work on organisational culture and leadership. He wrote a doorstop of a book about it and while it may not make your summer reading list, it’s worth a look if you have any interest in the influence of leadership on your company’s culture and performance.

According to Schein, culture is “a pattern of shared basic assumptions…and beliefs…a product of joint learning”. He observes that leaders have a disproportionate effect on culture because people look to them for the cues to their own behaviour. They basically replicate what they see up the food chain.

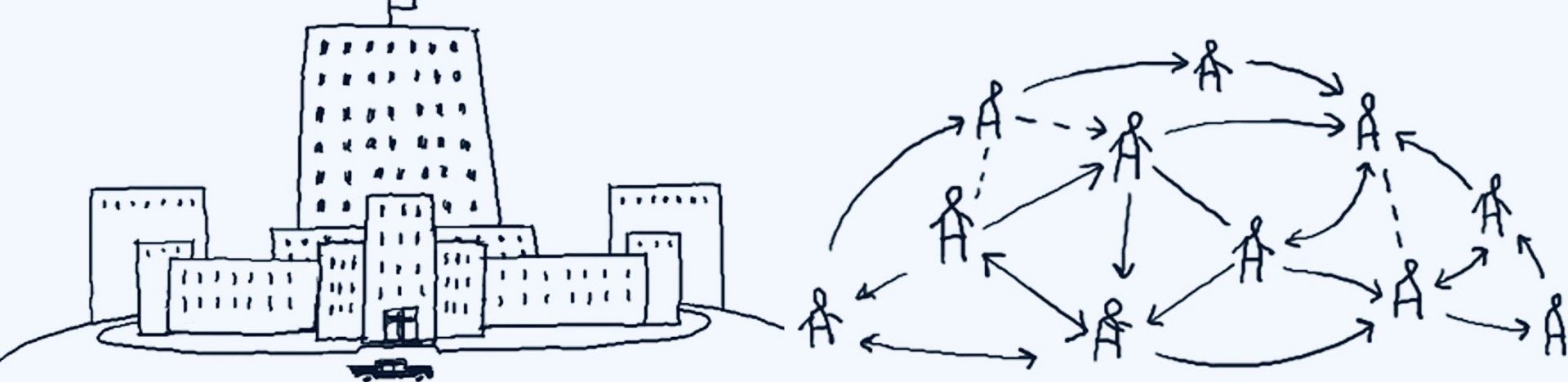

Although it was originally published in 1985, Schein shows great foresight when he points out that, “with the changes in technological complexity, the leadership task has changed. Leadership in a networked organisation is a fundamentally different thing from leadership in a traditional hierarchy”.

Today, most large corporates talk an awful lot about being a networked organisation. Buzzword bingo fanatics amongst you will observe that the word ‘matrix’ pops up a lot in the office, usually in juxtaposition to other words like ‘complex’ and ‘ambiguous'.

The reality is that many big companies, in spite of talking a good game, find it hard to shake off the comfort blanket of command and control, so deeply embedded is it in the organisational DNA. But shake it off they must, if they are to compete in a fluid and fast-moving world where upstart start-ups are darting into rockpools the FTSE 100 would rather they didn’t. The days of faux empowerment are numbered, it’s time to give the real thing a go.

Peter Drucker, whose name is 50% less stylish than Schein’s, is another management guru who understood the significance of culture in business. You will be familiar with his ubiquitous catchphrase: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”. I would add lunch and dinner to that itinerary. That’s not to say that Mr. Drucker believed strategy to be unimportant. It’s just that he believed a strong, empowering culture to be a bigger factor in long term success. It’s taken a while to catch on, (see paragraph above).

But do not underestimate its importance, as many leaders still so often do. Culture builds and culture kills, particularly in these connected times where everything that is said and done has the potential to circumnavigate the globe in less than thirty seconds. Sir Francis Drake, he of bowling fame, took three years to do the same. Times have changed and leaders must change with it.

A step in the right direction, of which fans of Sinatra’s Strangers in the Night have long been aware, is for leaders to pay close attention to do-be-do-be-do. Be who you say you are, do what you say you do, do it brilliantly well and do it consistently over time.

For those still in doubt, I throw these names your way as a gentle reminder: Enron, WorldCom, Bell Pottinger. I offer you another gift, the gift of wisdom: you can’t spin a better story, you have to be a better company.

It’s easier said than done because a company’s culture is made up of all the people, processes, systems and interactions that make up that company; the basket case potential is huge. But leaders set the tone and have the casting vote on what kind of a culture prevails – one that builds or one that kills.

Wise leaders will find their higher purpose, espouse values that people are excited to sign up to and show that big doesn’t have to be bad. In fact, with their culture in the right place, the biggest companies can be the greatest force for good in our society today. In these wobbly times, it is imperative they are.

I’ve worked with large corporates for twenty years. Generally, they are rational institutions which make informed and responsible choices about how to grow their businesses profitably. However, just like people, all companies have their idiosyncrasies. The one that stands out the most for me is what I call ‘The Hokey Cokey’. The Hokey Cokey (you put your left leg in) is a British dance, the popularity of which peaked in the music halls of the mid-1940s. Its novelty lies in its highly kinetic nature. Participants stand in a circle holding hands while performing the dance and as the chorus kicks in (Woah the Hokey Cokey!) everyone rushes into the centre and then back out again. The version of the Hokey Cokey I’m talking about relates to how Communication functions are restructured on a regular cycle, centralising (rushing in) and decentralising (rushing out). It goes a bit like this: A CEO is frustrated by how fragmented communication appears to be in the organisation. There are communications people everywhere who are costing the company a fortune, but none of their work is joined up and the result is a bunch of misaligned sub-cultures, often working against rather than in service of the organisation’s purpose and strategy. At this point, when the CEO’s annoyance peaks, the Head of Communications will be asked to bring the disparate communicators together into a centralised function to professionalise it and improve performance while reducing headcount and operating costs. (Usually around 30%). The customer-facing business divisions will (quite reasonably) be annoyed that they no longer have a communications team ‘outside their door’. Time will pass. The divisions may feel the new central team is somewhat distant from them. To counter this, a smart Head of Communications will put in place a strategic business partnering model to ensure a better level of support for the divisions while maintaining a central strategy and company-wide co-ordination. This is the sweet spot in the Hokey Cokey – when participants are neither rushing in nor rushing out. Things will go well for a bit. Then the CEO will kick-off a new strategic cycle. They will talk about how the world is changing and how the company needs to change with it to continue meeting the needs of customers. They will talk about the importance of simplifying the business and reducing costs while becoming more innovative and entrepreneurial. All of this is eminently sensible, which is why most CEOs say something along these lines when they announce a new strategy. The Transformation Programme will be rolled out. The CEO will observe how central functions have become bloated (which can happen) and how not enough of that investment is directed towards the company’s strategy and customers, (which can also happen). There will be talk of the need to refocus – fewer, better people doing fewer, more strategic things. The ExCo will support the CEO’s vision and embrace the initiative. Then they will summon the Head of Communications to discuss it, emphasising that if resource for their division is reduced further, they will jolly well go out and buy more resource themselves. (They just want to have a voice, after all). Even though the transformation is not about cost reduction, a number will be issued to the Communications team. (Usually around 30%). The Head of Communications will talk to the team about the importance of becoming leaner and more focused. They will also talk about the need to help the business divisions become more self-sufficient in their communications. The business divisions (quite understandably) do not want to become more self-sufficient. They don’t have the time or expertise. The Communications team no longer has the resource to support the divisions. A vacuum materialises. The divisions fill it by recruiting their own communication professionals. Communication starts to fragment. Global consistency is replaced by local primacy. The reduced central team struggle to maintain their relationships with the different divisions. Good work still happens, but there is less cohesion across the business. Over time, the number of communication professionals burgeons, far beyond the original level, as there is no longer central oversight. Then, at the start of the new strategic cycle the CEO observes that there are communications people everywhere who are costing the company a fortune…Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you the Hokey Cokey. Maybe this is simply the natural rhythm of the corporate world, like the cycle of the seasons or the rise and fall of a person’s breath. Or maybe there is a better way, that sweet spot in the Hokey Cokey where no one is rushing in or rushing out. A model that satisfies both group and divisional needs. One that balances global and local priorities, and connects the two. One with specialist expertise at the centre and partners out in the business with the resources to get work done. The constant centralise-decentralise spin cycle often spins up more problems than it solves and costs more than it saves. An intelligent communications model would take that insight on board and create the time and space needed to drive uninterrupted value for the organisation over several cycles, not just one. All together now…

While Rugby may not be everyone’s cup of tea, like any sport, it can often shed light on team dynamics, the importance of mindset and the nature of success. In 2003, England won the Rugby World Cup. The final was in Australia and I was not, so adjusting for the time zone difference, I threw a breakfast party for some friends. When Jonny Wilkinson scored a last gasp drop goal with the final kick of extra time, things went a little crazy. By the time I sat down again, Clive Woodward, the England manager at the time, explained what was behind the historic victory: “Winning is about inches. You can’t take short cuts if you’re trying to be the best in the world. We won by an inch, because we did that little bit more than our opponents”. I have a theory that Sir Clive’s inspiring assessment was itself inspired by Tony D’Amato. Tony doesn’t actually exist. He’s a fictional character played by Al Pacino in Oliver Stone’s film, ‘Any Given Sunday’. Tony manages the great Miami Sharks, currently struggling to make the American Football play-offs. He delivers what must rank as one of the greatest inspirational pep talks of all time, right up there with Shakespeare’s Henry V. “Life is this game of inches, so is football. Because in either game – life or football – the margin for error is so small. I mean, one half step too late or too early and you don’t quite make it. One half second too slow, too fast and you don’t quite catch it. The inches we need are everywhere around us. They’re in every break of the game, every minute, every second. On this team we fight for that inch. On this team we tear ourselves and everyone else around us to pieces for that inch. We claw with our fingernails for that inch. Because we know when we add up all those inches, that’s going to make the difference between winning and losing! Between living and dying!” You’d have to be a stone not to be roused by a speech like that, and Tony’s team does him proud by winning the day. It is a fitting cap to a career notable for its sustained success. A bit like Alex Ferguson. Only Sir Alex did it in real life. Sadly, the England rugby team still only has the one World Cup under its belt and has struggled for consistency over the past 15 years. The problem is that, while the team was set up to win in 2003, it wasn’t set up to maintain that level of success. It peaked. Then it troughed. New Zealand, on the other hand, are a different proposition entirely. They just keep winning, match after match, generation after generation. They have won more World Cups than anyone else, including back-to-back victories in 2011 and 2015. They won the old Tri-Nations championship 10 times, while Australia and South Africa managed only three apiece. Since Argentina joined the party in 2012, the All Blacks have won the championship a further six times. They also have a ridiculous win percentage in test matches at 77%. And New Zealand holds the record for the most consecutive test wins at home – a 47-match winning streak, achieved between 2009 and 2017. All this by a team from a tiny South Pacific country of 4.5 million people. The answer to such astonishing and sustained success can be found in a culture of winning that was established early in the team’s history through the ‘Originals’ team of 1905 and the ‘Invincibles’ of 1924. This created a sense that they could achieve anything. It didn’t come from the coaching staff; there weren’t any coaches back then. It came from the players themselves, who set the standards and the values of the team; values that have remained constant for more than a hundred years. That sense of ownership and inclusivity is crucial to a winning team mentality. It is the bedrock of belief. If you don’t believe, you can’t win, no matter how skilful you are. And it’s not just a mentality adopted by the team. Over the years, the belief that New Zealand is the greatest rugby nation on earth has transcended the boundaries of the game and infiltrated every corner of the country’s social and cultural fabric. It is more than expectation. It has become received wisdom. The self-belief that goes with pulling on the famous All Blacks jersey is coupled with an unwavering commitment to being part of a team. New Zealand internationals don’t aspire to personal greatness, they aspire to collective greatness. There is a relentless focus on being greater than the sum of their parts. The selfishness and ego of the individual have to be put to one side. The team always comes first. Another quality has been the All Blacks’ ability to continually adapt. The world is changing at an ever-increasing rate. Rugby has evolved at an astonishing rate alongside it. It’s unrecognisable from where it was in 2003. Former England player, Austin Healey, made the observation that changes to conditioning, sports science, tactical thinking and rules mean rugby is a completely different beast compared to three years ago, let alone a decade. To keep winning as the world changes around it, a rugby team has to keep re-inventing itself. Like the sporting equivalent of Madonna or U2. That requires a commitment to lifelong learning and a growth mindset so that neural pathways maintain peak elasticity. In the modern era, under Graham Henry and now again through Henry’s prodigy, Steve Hansen, the All Blacks remain resolutely committed to learning and improving. Continuity and stability are important, which is what you get from a strong culture and values. But getting set in your ways is a killer. When we find a winning formula, it’s tempting to stick to it. Your brain tells you that what caused you to win in the past will help you to continue winning in the future. Which, of course, will only be the case if we somehow manage to put the world around us on pause. That’s not going to happen so it’s a case of adapt or die. Just ask Kodak. Click. Constancy of values. Collective belief. Primacy of the team. Commitment to learning. Continuous adaptation. Strong and consistent leadership from coaching staff and players. All are vital ingredients of a team that keeps winning over time. Succession is the final piece of the puzzle. At the time of the 2011 World Cup, the BBC’s Tom Fordyce observed that rugby grabs Kiwi kids young. Community rugby programmes are handsomely funded. Every single primary school has a grass playing field. Rippa Rugby – a simplified, non-contact version of the game – was invented to make rugby as easy to play and as much fun as possible. There’s a feeder system for talented young players too, the ingeniously titled ‘Small Blacks’. The fundamental point here is that you can only get a return on investment if you invest in the first place, and keep investing. Lasting success doesn’t come through one magical flourish but through a combination of many factors from the grass roots to the dressing room. It is in the never-say-die mentality of all who play the game. It is in the pride felt by those who pull on the shirt for their country. It is in the blood of the whole nation and their faith is unshakeable. It comes as no surprise then that the mighty All Blacks are odds on favourites to win their third consecutive World Cup in Japan this autumn. They will fight for every inch. I wouldn’t bet against them.

There’s nothing quite like the impending threat of global destruction to bring out the best in people. I went to watch Avengers Endgame with my family at the cinema recently. As I watched the story unfold, it struck me that Marvel’s mega blockbuster has a thing or two to teach us about building a successful team . The Avengers line-up has grown somewhat since they first assembled. The core team of Captain America, Iron Man, Thor, Hulk, Black Widow and Hawkeye has now been joined by Captain Marvel, Black Panther, Spiderman, Antman, Dr Strange and the Guardians of the Galaxy. What hasn't changed is that they are all strong characters with very different and highly competitive personalities. It's a sure-fire recipe for conflict rather than co-operation, and we've seen that play out in each of the four Avengers films whether it's Tony Stark and Steve Rogers falling out over the issue of superhero regulation or Thor getting sideswiped by Hulk. And yet, by the time the credits roll on Endgame, the Avengers have overcome their differences and defeated the biggest and baddest villain in the universe. What on the surface looks like an entirely discordant team, turns out to be very much greater than the sum of its parts. So how does that work exactly and what can we learn from it? Here are some of the qualities that make the Avengers a world-beating, universe-saving team. Strong Leadership - corralling a bunch of superhero hotheads into a cohesive unit requires a leader with deep experience and real strength of character. If you cast your mind back to the first film, you'll remember that the original Avengers were brought together by Nick Fury. As a decorated General, Fury has plenty of experience of leading teams through war and peace. He knows bringing a highly skilled group of individuals together won't be enough on its own. He also rallies them behind a common purpose, sets a clear strategic objective and puts in place an ethical framework. And then when it's time to swing into action, Fury lets the Avengers get on with it, knowing everything is set to guide the team in the right way - that's empowerment in action right there! Clear Identity - as the great Tony Stark once said: "The Avengers. It's what we call ourselves. Sorta like a team. Earth's mightiest heroes type of thing". The name of the group is a unifying label and badge of honour that gives its members a sense of belonging to something greater than themselves. Inspiring Imperative - it doesn't get bigger or more inspiring than saving the universe. It's a mission purpose-built to get the passion flowing and the action rolling - who wouldn't want to be part of it? Teams perform at their best when they come together around something they truly believe in and which inspires and energises them. I experienced this at first hand during the 2012 Olympics when I was consulting with Transport for London. What began with disaffected colleagues and a glut of Union strike ballots before the Games, became a template for how to mobilise a team of 40,000 and work in unison to deliver an unqualified success. Team Work - the Avengers are a diverse and volatile mix of big egos but they work hard to overcome their differences and leverage their respective strengths to the maximum. There's an incredible scene in the first film, as the aliens are wreaking havoc in New York, where the team really comes together. As Iron Man "brings the party" to the invaders, Captain America co-ordinates the team effort. Thor battles the airborne aliens, Black Widow runs the ground offensive, Hawkeye has his colleagues' backs from the rooftop and Hulk smashes at the appropriate moments. It's a team working in perfect synchronicity. Each person understands the part they play and how that fits into the big picture. Effective Communication - there's a rhythm to how the different versions of the Avengers team develops in each of the four films. At the outset, there is usually discord between established members and friction as new ones join. Communication is challenging and rarely effective. It leads to dysfunction and underperformance. Then as the films progress, the team begins to open up. Through the many perilous challenges they encounter, they get to know each other better, learn to appreciate one another more, set their differences aside and share more readily. This builds the foundation of trust and respect that ultimately makes the team so successful time and again. Succession - highly effective teams are ones that continue to adapt and evolve over time, nurturing new talent, bringing it through the ranks and promoting it into leadership roles when the time is right. During Endgame, Thor hands the leadership of Asgard to Valkyrie. Similarly, towards the end of the film, we see an elderly Steve Rogers pass Captain America's shield to Sam Wilson. Without succession, no team can sustain success over time. If ever there was an example of a tight-knit unit with real purpose, drive and determination, the Avengers are it. Steve Rogers perfectly encapsulates this in his pep talk before the group goes back in time to secure the infinity stones: "This is the fight of our lives. We are going to win. Whatever it takes." Smells like team spirit to me.